Vanlife access and wildlife threatened by 3.3M acre federal land selloff

A proposed plan by the U.S. Senate to sell 3.3 million acres of public land has sparked widespread concern, as it threatens wildlife, fragile ecosystems, and puts at risk public land access for vanlifers, overlanders, and outdoor travelers who rely on these spaces for free camping, off-grid living, and seasonal movement.

Introduced in June 2025, the bill would authorize the sale of up to 3.3 million acres (about 13,400 km²) of federal land over five years, targeting areas managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). The areas at stake include many of the forests, deserts, and mountain zones relied upon for free camping, off-grid access, and the wide open spaces that define vanlife.

What exactly is being proposed

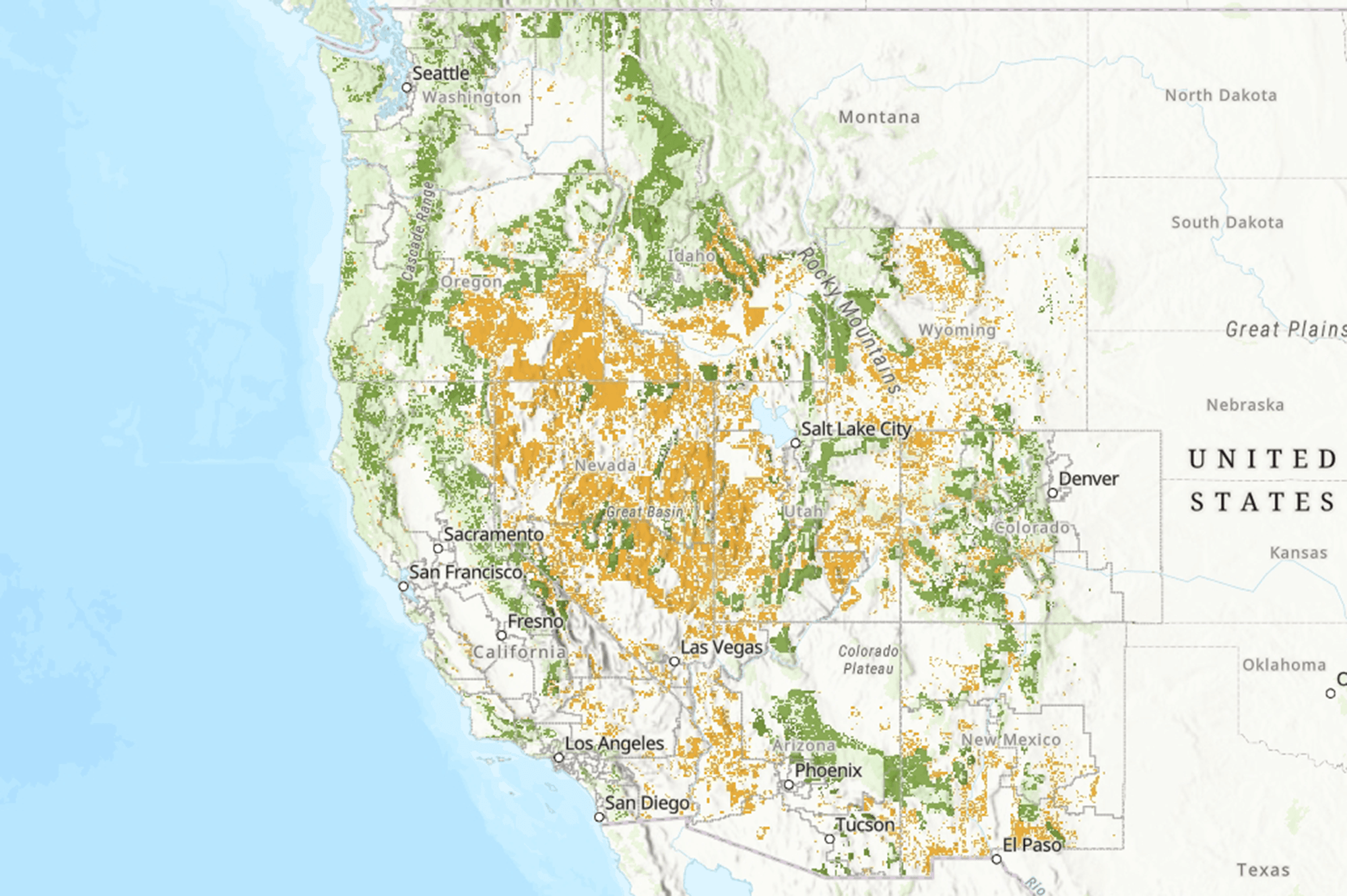

The provision is included in the Senate’s version of a larger budget reconciliation package. If passed, it would require BLM and USFS to sell or transfer between 0.5 and 0.75 percent of their holdings over a five-year period. That translates to roughly 2.1 to 3.3 million acres (about 8,500 to 13,400 km²) across 11 Western states, including California, Utah, Oregon, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Washington, Wyoming, Idaho, and Alaska.

While the bill mandates the sale of up to 3.3 million acres over five years, conservation groups warn that the pool of land eligible for sale is vastly larger. According to the Wilderness Society, more than 250 million acres of BLM and Forest Service land across the 11 targeted states meet the bill’s vague criteria and are technically at risk. These include wilderness study areas, wildlife corridors, roadless forests, and other ecologically or recreationally valuable spaces that lack formal protection. The bill does not require public review or environmental screening for selected parcels, meaning any tract not explicitly excluded could be nominated for sale.

The proposal specifically excludes national parks, designated wilderness areas, and lands with certain active leases or infrastructure corridors. However, lands with grazing permits are no longer fully excluded under the current draft of the bill, meaning grazing allotments may still be subject to sale. Montana is also exempt.

However, the land that remains “on the table” includes some of the most accessible and scenic zones used for dispersed camping, boondocking, and off-road recreation. These are the kinds of places where vanlifers stay for free, often without amenities but with views, quiet, and freedom.

Why it matters to vanlife and overlanding

While the scale of the proposal is smaller than some initially feared, 3.3 million acres is still a significant area and the risk to public access is very real. Vanlifers often rely on BLM and Forest Service land to camp legally and affordably, especially in states where campgrounds are overcrowded or prohibitively expensive. Many of the areas potentially at risk are the forests near Tahoe, the plateaus outside Moab, and the remote trails of Oregon’s high desert.

If these lands are sold to private buyers or transferred to state control, they could be closed off entirely or subjected to new restrictions. States may introduce camping fees, require permits, or ban overnight stays, though policies would vary by jurisdiction. In some cases, land could be leased or sold for mining, development, or other industrial use.

Although the bill requires federal agencies to consult with tribal nations and coordinate with state and local governments, the budget reconciliation process allows the broader land sale mandate to advance without traditional public hearings or environmental review. There is no guarantee that access will remain after the land changes hands.

Economic impact on local communities

Beyond vanlife, the proposal also threatens parts of the US$1.1 trillion outdoor recreation economy. Towns like Moab, Bishop, Bend, and Durango are economic engines that rely on steady access to surrounding public land. If the free, open spaces disappear, so too might the steady stream of travelers who fill local coffee shops, grocery stores, laundromats, and repair garages.

Conservation groups warn that this could lead to cascading economic losses in rural regions. At the same time, more travelers may be forced into fee-based campgrounds or private land rentals, raising the cost of life on the road.

Environmental concerns add to the pressure

Public lands marked for sale or transfer are not just important for camping. Many serve as wildlife migration corridors, watersheds, and buffer zones between development and protected ecosystems. Once federal ownership ends, those protections can disappear.

Environmental groups including the Grand Canyon Trust, Center for Western Priorities, and Outdoor Alliance have raised the alarm over the potential for deforestation, habitat loss, water pollution, and fragmentation. In areas already stressed by drought and climate change, these impacts could be irreversible.

Indigenous rights and consultation

Another critical issue is how the proposal affects Indigenous communities. Much of the land under review overlaps with ancestral territories and sacred sites. While the bill requires tribal consultation, it does not ensure that treaty rights are upheld if the land moves into private or state hands.

Federal agencies are legally obligated to respect tribal sovereignty and cultural access. States are not. Once land changes ownership, tribes may lose access entirely, or face new barriers to visiting or using these lands.

Several Indigenous leaders have criticized the bill for ignoring the historical context of land dispossession and warned that this process risks deepening the disconnect between tribes and their homelands.

Legal controversy and lack of transparency

Critics have also taken issue with how the legislation is being advanced. By embedding it within a budget reconciliation bill, the Senate has bypassed normal public hearings and agency review. This approach limits public input and fast-tracks what would normally be a lengthy land management debate.

Legal experts point out that the U.S. Constitution’s Property Clause gives Congress authority over federal lands, and critics argue that this scale of land liquidation without thorough debate, planning, or local consultation could violate the spirit of existing public land laws. Legal action may arise if the implementation process violates other specific protections, particularly around tribal consultation or environmental compliance.

Earlier this spring, the House version of the budget package included a smaller land transfer proposal covering just 500,000 acres (about 2,000 km²). After strong public backlash, that language was removed. The Senate’s version, however, reintroduces the issue at a larger scale.

What happens next

The future of the proposal is still uncertain. The House and Senate will need to reconcile their versions of the budget bill, and it remains possible that the land sale language could be altered or removed in that process. However, if passed into law, the consequences for public access would likely be permanent, as privatized lands are no longer federally managed or open by default.

Outdoor Alliance has called this the most serious threat to public land access in decades. While only a few million acres may be sold or transferred initially, the broader concern is that the precedent would make it easier for future administrations to reduce public access even further.

What you can do

Advocacy organizations have already launched public campaigns to stop the proposal. Vanlifers, overlanders, and road travelers are encouraged to contact their elected officials, share their stories, and support legal and grassroots efforts to protect public land. Outdoor Alliance has provided a simple way to send a message to Senators.

For many, public land is not just a place to camp. It is a foundation for freedom, mobility, and connection with the natural world. This proposal may not be the end of dispersed camping, but it could change the landscape for generations if left unchallenged.

Comments

No comments yet